Yeah, it's evil

But not in the way that Georgia sheriff seems to think it is

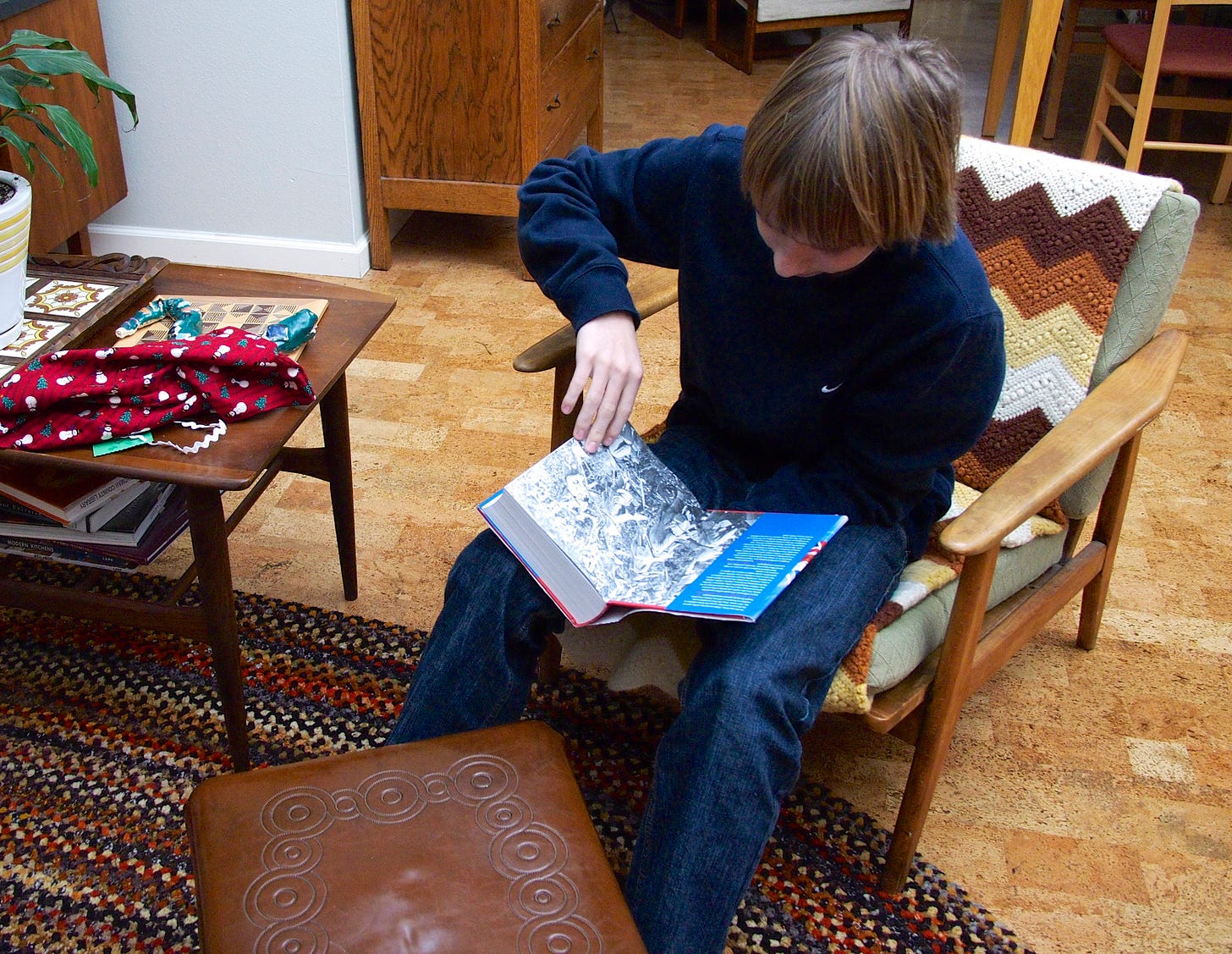

If you knew my son at 14 or 15, you know this: He was a child, not an adult. You saw it in the smoothness of his skin, the fringe flopping over his eyes, the slope of his slender shoulders. Other boys his age might have looked older, but inside they were all still just boys, at the beginning of transforming into men.

If you’ve been reading my words for any length of time, you know that school shootings are always personal to me. Like so many, I have become numb to so many terrible things happening in our world, but very single school shooting makes me cry. I spent 31 years working in school buildings, and I can never read of a school shooting without picturing the staff and students I spent those years with. Without remembering the lockdown drills, the way I came to search any unfamiliar person for signs of danger, the way it became reflexive to scan for escape routes in any building I found myself in.

For many of those years, I taught high school freshmen. Boys the same age as the one who just killed 4 people in a Georgia high school.

Boys. They were in no way adults. Anyone who has ever raised a boy must know this. And yet, here we are, supposed to take comfort from the announcement that the boy who has wreaked havoc on his community and any of us with personal connections to schools will be tried as an adult.

In my first year of teaching, one of my students shot and killed another one. They were both freshman boys. They went in a rock quarry on the mountain about a half hour out of town. There were some drugs and, obviously, a gun. The boy who did the shooting was a quiet, thoughtful person who sat in the front row and turned in his work and always spoke respectfully to me. I never witnessed any behavior anyone might call unkind. The boy he killed was a boisterous, goofy kid with bleached hair who often didn’t do his assignments. I knew he was a little troubled and sometimes he caused some trouble, but I liked him. I liked both of them.

I will never forget learning about what happened to them in my first (but, sadly, far from last) “stand up meeting” after school. We all filed into the choir room. Older teachers knew that a stand up meeting is never called to share good news. Its purpose is always to get hard information out quickly and in one place, so those in charge can know what was said to staff and give them directions about what to say in response to news that will quickly spread. I remember gasping, saying some words out loud. No one else did. It was the only time I did such a thing. First times are like that, but I learned quickly.

When I was pregnant with my son, the only boy name my husband and I both liked happened to be the name of the student who killed my other student. For months, I resisted that name. How could I give my son the name of a killer? How could I attach any part of the life I was creating—the one I had such high, high hopes for—to one that had gone so horribly wrong?

Eventually, though, I did. It was a name that had more important meanings to us, and I decided to let those carry more weight. Now, more than 26 years later, I also know this: The quiet, thoughtful, kind boy in the first row that I knew was just as real as the one who killed his friend when he was only 14. He wasn’t a mask that an evil boy was hiding behind. He was a young boy who did a reckless, impulsive thing, as so many boys—including my son—do on their way to becoming men. Most of the time, the damage from those actions is minor or fleeting. Sometimes, though, it is tragic.

I am no longer the idealistic, naive teacher who gasped out loud in the choir room. I do not believe that all we need is love. I believe in holding children appropriately accountable for their choices, even impulsive ones. I know that some humans lack the empathy that keeps most of us treating each other decently most of the time, and that they show signs of this as children. I am pretty sure that at least two students I taught fall into this category of people. I will never, ever forget the devastation I saw on a friend and colleague’s face after a shooting in the school his child attended. One school I worked in was later shot at by a student, and one principal I worked for experienced one of the first school shootings that became national news. Every morning, I send my husband to school and every day I hope that he will return safely home to me, knowing that I cannot take his safety for granted. Every time I have an outsized startle response to normal, every day noises, I know that my complex PTSD was formed, in part, by my years of working in schools in the years after Columbine. School shootings are never, ever an abstraction for me, a theoretical. The years of ever-increasing drills, cameras, and security measures made them real.

And I am so sick and tired of us pointing the finger of blame at children we have failed to protect. Of us traumatizing a whole generation of children with our drills and repeated acts of violence because we will not take the actions we need to take to make our schools and communities safe from gun violence in the ways previous generations did. The real evil is not in a boy who is in no way an adult, but is in the ways in which we allow those who monger fear in order to protect their own power and wealth create a world in which most of us no longer even pay much attention when children to go into schools and open fire.

When my children were young, I put plastic protectors in all our outlets. I had a safety gate to keep them from venturing up our stairs. I didn’t allow any toys with small parts until they were past the age of choking on them. I kept close eyes on them. When they melted down or behaved “badly,” I looked for the bigger picture of the behavior and sometimes made changes in my own as a result. I did not write them off as “bad kids.” Yes, it got harder as they got older, but I never stopped trying to do what I could to keep them safe, as we do for children we love.

Yesterday I asked my son if he had heard about the school shooting.

“Isn’t there one like every day?” he said.

I remember what it was like when we all gasped at school shootings the way I did in that choir room 33 years ago. I remember enough to know that our country can be a different kind of place, but my son already accepts that how we are now is just how it is.

That’s part of this tragedy, too, and one that will allow the killing to continue.

Fourteen. FOURTEEN. That is what my mind keeps going to, too, in the midst of hearing about this. What kind of surreal reality when we've all become so numb to news like this. I am so deeply grateful for your words. I know the absolute heartache you must have felt writing this, so please know I read every word and I am holding it all tenderly.

It's chilling how normalized these tragedies have become. I was a junior in high school when Columbine happened and therefore got to live the majority of my school years in safety and ignorant bliss. How f'd up it is that in our country the price of sending your kid to school (or becoming an educator!) is terror, fear, stress and the constant threat of potential violence. There has to be a better way!