Everyday Use

Of legacies and the objects that embody them

“I often ask myself, Will anyone I know be happier if I save this?”

― Margareta Magnusson, The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Free Yourself and Your Family from a Lifetime of Clutter

What do I know of my great-grandmother Anna Emilia Schmitt, born in 1878?

She came to the United States from Germany with her sister. They came to work as servant girls, she in a house with a kindly husband and a stingy wife. The servants were allowed to eat leftovers from the main meal of the day, but the wife frequently forbid them from eating any meat that remained.

One day, as Anna cleared plates with a good amount of meat left on them, the husband said to her, a devout Catholic, “Ah, Anna, too bad today is Friday and you can’t eat this meat.”

She replied, “Sir, every day in this house is Friday for us.”

The wife was not pleased.

I know that Anna and her sister went back to Germany to marry two brothers from their village, and then she and her husband returned to British Columbia, Canada, to homestead. They nearly starved one winter, and they ended up in Pt. Angeles, Washington. There they continued to struggle, but according to my grandfather they stayed because “she refused to move from a city named for angels.”

She was not an easy woman. She would not form friendships with any who were not, like herself, German Catholics. Her first three children, all girls, completed college educations. When my great-grandfather was killed in a construction accident, my grandfather had to leave the Jesuit boarding school he’d been sent to (as a response to some bad behavior) and return home. He went straight to work when he finished high school. When my grandmother married him, her new mother-in-law apologized for his lack of a college education, as if it were her personal failing. Once, when I made a face at the asparagus my grandmother had made for dinner, my gentle grandfather sharply rebuked me, something he never did; later, he explained that if he had done such a thing when he was my age he would have been sent to bed by his mother without any food at all.

Anna died at the age of 95, when I was 8 years old. I have a few vague, hazy memories of her, and these few brief stories. I also have a quilt she made.

In Alice Walker’s short story “Everyday Use,” (published by Harper’s in April, 1973, the same year my great-grandmother died) a young, Black woman comes home to visit her mother and sister in the country. The woman, originally named Dee and now calling herself Wangero, is college-educated and lives in the city. Her mother, the narrator, lives with her other daughter in a 3-room house; she can fell a bull calf with a sledge hammer, among other things.

Wangero wants Mama to give her two quilts pieced by her grandmother, but the quilts have been promised to her sister, Maggie, who “knows she is not bright” and is soon to marry a young man “who has mossy teeth in an earnest face.” Mother and daughter argue about who should get them. Wangero is appalled by the idea that Maggie might have the quilts, which contain scraps of clothing worn by their ancestors:

“‘Maggie can’t appreciate these quilts!’ she said. ‘She’d probably be backward enough to put them to everyday use.’”

Wangero wants to preserve the quilts. She tells her mother that she would not sleep under them, but would hang them on a wall.

When I was in my early 20’s, my grandmother gave me a quilt that my great-grandmother Anna had pieced but never quite finished. It had a backing fabric sewn to a quilt top, but no batting between them, and no quilting to hold them to each other.

I used the quilt as it was, but it did not last long. I moved frequently and lived in the kind of hard way many do in their first decade of adulthood. The fabric was thin, and the pieces were joined by hand-stitching. It was delicate. I called it my ugly quilt, as I could see nothing pleasing in its riot of clashing colors and patterns. Still, when it began to fall apart, I knew I’d mistreated something I should have better cared for.

I thought of the two sisters in the Alice Walker story I’d read in college, hating to think I had been like the slow, dim sister destined to marry a boy with bad teeth—even though, when I’d first read it, she was the sister I felt more sympathy for. I did not want to be like Wangero, who I’d seen only as cruelly arrogant, but I’d come to see that perhaps she’d had a valid point.

In her essay “In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens” (1972), Alice Walker explores the legacy of Black women artists (“artist” denoting who one is, rather than what one does) denied the material conditions needed to create the kinds of work we define as art (paintings, poems, essays, musical scores, novels, etc.). Writing about an anonymous Black woman who created a quilt that hangs in the Smithsonian, Walker states that she “left her mark in the only materials she could afford, and in the only medium her position in society allowed her to use.”

I read this essay not long before I became the keeper of Anna’s quilt. My great-grandmother was neither Black nor a slave, but like Walker’s ancestors, she lacked the kind of materials and position she would have needed to create traditional works of art. One day, remembering the essay, I began studying it for possible clues to the woman who’d created it.

Only then did I see that the placement of color and pattern was not random. Only then did I see that there had been an attempt to create something pleasing from a jarring array of fabrics. I thought I saw that the most subdued fabrics were at the outer edges, while the most vibrant—tomato reds, deep navies, thick white stripes and polka dots—were in the center of the quilt. I wondered if it had been a kind of self-portrait, if the young woman who had spoken sassily to her employer had remained alive inside the staid woman—my father’s Nana—she became.

I wrote a poem about the quilt, wanting to honor in her and her experience what Walker said her mothers and grandmothers had given to her: “the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see… .” I wondered what she might have created if, like me, she had been able to go to college and work and create with words.

And still I wrecked it.

About 15 years ago, I received a box in the mail from the daughter of one my great-aunts. Her mother was my grandfather’s sister, one of the three who earned college degrees. I didn’t remember ever meeting her, although I probably did as a child. By 2009, that branch of my family tree existed far from the trunk of my life. I hadn’t seen any of them for years.

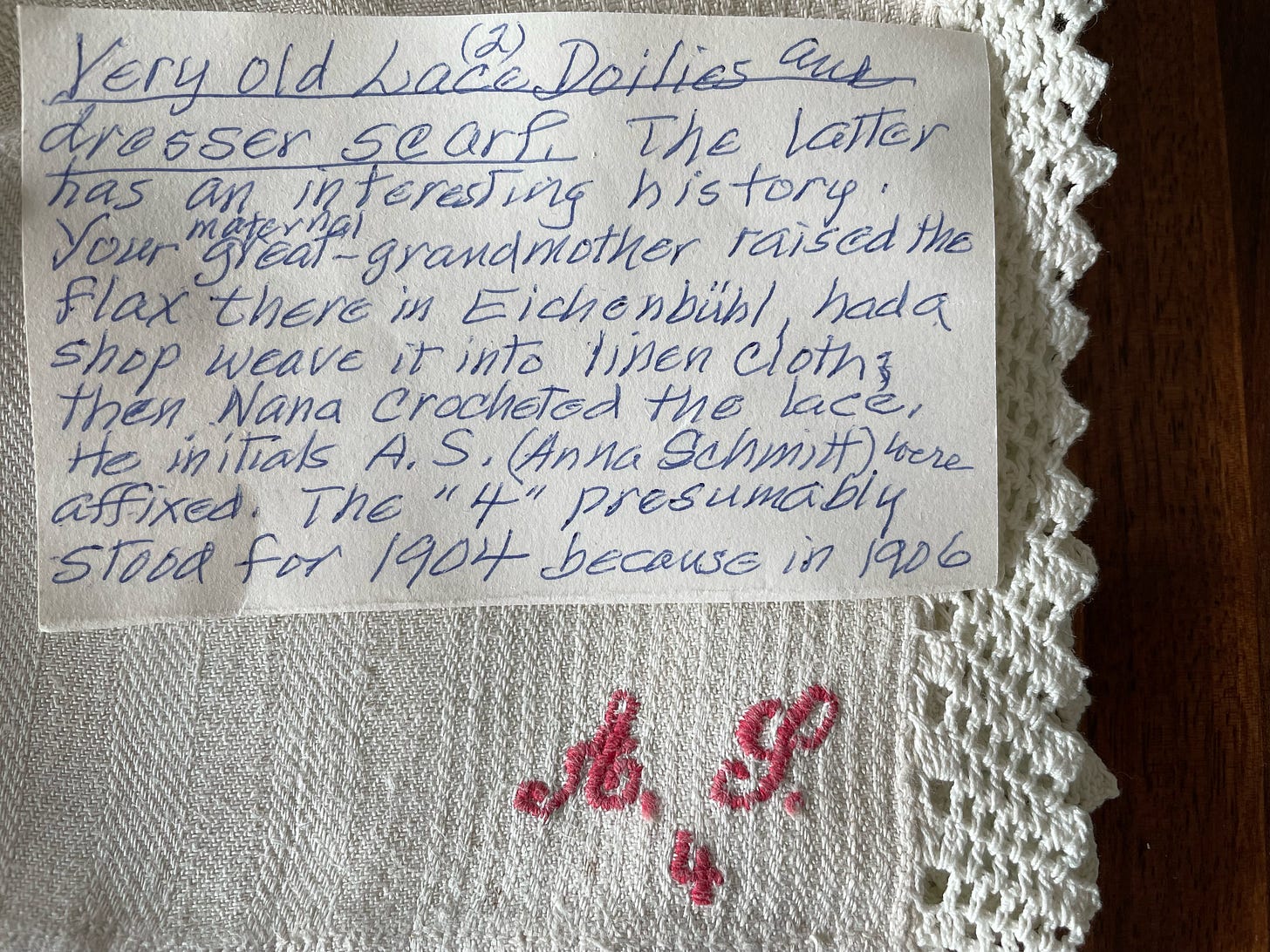

In the box were things my great-grandmother had made—lace, a small wool rug, doilies, and a quilt similar to the one I’d ruined. There was also a china plate and a teacup and saucer that had traveled to the United States from Germany more than 100 years earlier. A note said that these items had been especially treasured.

The note also said that she believed I was the best person to be the caretaker of these family treasures.

I was recently divorced, and it seemed to be a time of second chances. I promised myself I’d do better with these things. I left them in their box and tucked them safely away.

A few years ago, after moving to the house I live in now, I took the surviving quilt out of the box I’d been storing it in. It felt wrong to keep it there, and I wondered what I was keeping it for. So one of my children could one day keep it in a box? And would they even want to keep this rough, unfinished relic from a woman they had never known? A woman I had almost no memory of? It was a few years before The Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning would have many of us pondering such questions, but I suspected that any meaning beyond the practical that this quilt might have would die with me, the end of the line of descendants who had known Anna.

I draped it over the foot of a bed, just as it was, and told myself that I would finish it. After all, I had some experience with quilting. In those few, fleeting years between college and teaching, before the demands of working and adulting severed threads stitching me to my childhood avocations, I loved reading about quilting and had made a few small pieces. A few years after that, I married a man with a little girl, and I made a whole quilt for her after her mother died.

I should be able to finish Anna’s quilt, right?

I couldn’t do it. It was oddly constructed, and finishing it would mean cutting the fabric, not just undoing seams. I couldn’t see a good place for doing that, and I was afraid I would ruin the quilt and, not knowing how to fix it, abandon the project.

And so, like Wangero wanted to do with her mother’s quilts, I hung it on a wall, draping it over a curtain rod, afraid that if I hung it from hooks the weight of the piece would pull already-fragile fabric away from stitches that have come loose. I did this in the fall of 2019, when I was turning a small bedroom into a space for working on creative projects. I liked the idea of my great-grandmother’s creative work adorning the wall in the room where I hoped to make things.

In March of 2020, that room became my work-from-home space when the pandemic closed schools; the quilt became my backdrop in every Zoom meeting I would participate in until we returned to our buildings in the spring of 2021. That same spring, my son came to live with me after leaving the Marines, and then my husband and I married and he moved his things into our small home. I no longer had the literal or metaphorical space for creating in the way I once did, but I left the quilt hanging there.

Not long ago, my husband and I decided to finally clear our garage of things we’d put there because we’d had neither time nor space to figure out a good place for them. There were pieces of furniture from his house that we finally acknowledged were never going to have a place in the one we now share, and there were boxes of old memorabilia from both our lives that we finally felt ready to sort through.

In one box I found the poem I’d written as a young woman about my great-grandmother’s ugly quilt. I’d printed the poem and framed it, with a mat I’d covered in scraps from the quilt. I’d given it to my grandfather for a birthday present in the early 90’s, and it hung in my grandparents’ home until my grandmother’s death in 2018, when it came back to me.

I didn’t know what to do with the framed poem. Back when I wrote it, I hoped that I, like Alice Walker, might some day own a collection of books with my name on the spines. I did not like Wangero, but back then I identified much more with her than with her slow sister Maggie, who was content to sit on a porch in the evening with a lip full of snuff.

I had no idea what was coming for me, how the invisible trauma markings of my forebears would express themselves in my life through unhealthy marriages and an inability to extract myself from places that weren’t good for me. I didn’t know that education wasn’t the magic ticket to a good life that my parents and grandparents seemed to think it would be, and that teaching and mothering would, for three decades, use up nearly all of my physical and creative resources. I didn’t understand that I was going to be more like Anna or Maggie than Alice or Wangero, and was not going to have the conditions I would need to create a kind of art that might last beyond my time.

I didn’t want to display the framed poem, but it also felt wrong to throw it away. There were those scraps from the quilt surrounding it. Both my words and her textiles feel like artifacts that might be important to keep. It’s now up in my attic, waiting for me to decide what to do with it.

The room where the quilt hangs is no longer a work office, but it is still not a room for creative projects. My daughter moved into our spare bedroom after my son moved out, and I put a single bed in that little room to use for isolation when someone in the house contracted Covid. I’ve kept it there for the nights when my insomnia and/or my husband’s snoring make sleep in my own bed impossible.

The room has a south-facing window, and many afternoons the quilt spends several hours in indirect sunlight. I’ve wondered more than once if I’m doing a disservice to it; I know the light will contribute to its deterioration.

Then I think of Alice Walker and her mother’s gardens, the inspiration for her famous essay. I remind myself of her words:

I notice that it is only when my mother is working in her flowers that she is radiant, almost to the point of being invisible-except as Creator: hand and eye. She is involved in work her soul must have. Ordering the universe in the image of her personal conception of Beauty.

Her face, as she prepares the Art that is her gift, is a legacy of respect she leaves to me, for all that illuminates and cherishes life. She has handed down respect for the possibilities-and the will to grasp them.

Can any work be more transient than a garden? And yet, how stark the world would be without their blossoms. Permanence, I know now, cannot be the determinant of artistic value, for either a creator or an audience.

Part of the reason I have not transformed that room back into a space for creative work is that I still cannot separate it from that year of remote work so crushing I finally left education, as, perhaps, I should have done years earlier. I write these words sitting at our dining room table, in front of a window that gives me a view of squirrels, rabbits, birds and the garden we’ve grown for them to live in. Right now I see, at the beginning of the winter of my life, the first spring buds getting ready to bloom.

I think now of another writer important in my youth, Anne Tyler, and of her essay “Still Just Writing.”

“I was standing in the schoolyard waiting for a child when another mother came up to me. ‘Have you found work yet?’ she asked. ‘Or are you still just writing?’”

The essay is in a book I bought nearly 40 years ago, a collection of essays by writers on their writing.1 For years I read and re-read the words of those writers, especially the women: Adrienne Rich, Mary Gordon, Francine Du Plessix Gray, Maxine Kumin. Of course, predictably for that time, all of the women are white, and many, like Tyler, are not solely responsible for their own financial support. I overlooked that then, as well as these words from Tyler, writing about the luxuries she enjoys as a writer supported by a husband: “The only person who has no luxuries at all, it seems to me, is the woman writer who is the sole support of her children.”

What I want to say to that young woman I once was, the one who would become a single mother and was never without a job (or two) from the ages of 15 to 58—and to all the young women I see now agonizing over how to make it all work, how to make space for all they want and need to do—is that you are going to do what you are able to do, and whatever that is will be enough. It will be enough to matter in ways that matter.

I don’t have a shelf filled with books that I have my name on the spine, but here I am, still writing, still sharing my gift. I think of my daughter, who never knew Anna, but who designs and adorns clothing from scrap yarn and thread that other family members have donated to her. Like Anna, she paints with fiber and needle. Every day I walk by the door to the small room that might yet become a creative studio and see my great-grandmother’s quilt hanging on the wall, which reminds me every day to think about how I want to spend the ones that are left to me. Often, that is enough to send me here, to my garden of words and memory, where Wangero and Maggie are not two poles of a dichotomy, but two parts of a whole, and where there is more than one way for a quilt to be of everyday use.

If my thoughts spark some of your own, please share them in the comments. I like to think of these writings as an invitation to a conversation.

I would especially love to know what you think about creative legacies—your own, or those of others who came before you. And what do you do with family stuff, if you have it?

But really, I love to read any responses you have to my words.

If you like this post, please click on the heart ❤️ and/or share it! Doing those things helps more people see it. It also gives me encouragement to keep going. Think of it as throwing some metaphorical spare change into the hat of a street musician.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, I hope you’ll sign up to receive notices of new posts. Everything here is free.

First Person Singular: Writers on Their Craft, compiled by Joyce Carol Oats. Ontario Review Press, 1983.

Yes you are completely right. I wasn’t looking at it that way, but yes!

Why can't we live closer so we can discuss these amazing posts over coffee, tea, or pie?

Women have definitely evolved over time. I think that in the last 53 years, I have lived many lives, if that makes sense. I didn't particularly like Anna (yours, not mine). But then I think about my grandmother, and after doing soul homework, I realize I don't really like what she's said or done to my mother. NOW, times were very different, and they were under far more pressure in society and at home than we can imagine. It's just interesting to hear these stories. You write so beautifully and you make it sound like it happened last week, which is why it's so interesting.

That quilt is lovely. I have the quilt that my grandmother made for me and my ex-husband for our wedding on the bed in Anna's room/my office. I look at it every day. The dogs lay on it. It gets used. I don't think my grandma would like that. I love it.

I was going to write something else, but the post disappears when I comment, so I'll have to publish the comment and come back. Brain fog is the worst.