Getting small to go big

How my small life (and heart) has expanded in ways I didn’t think were possible

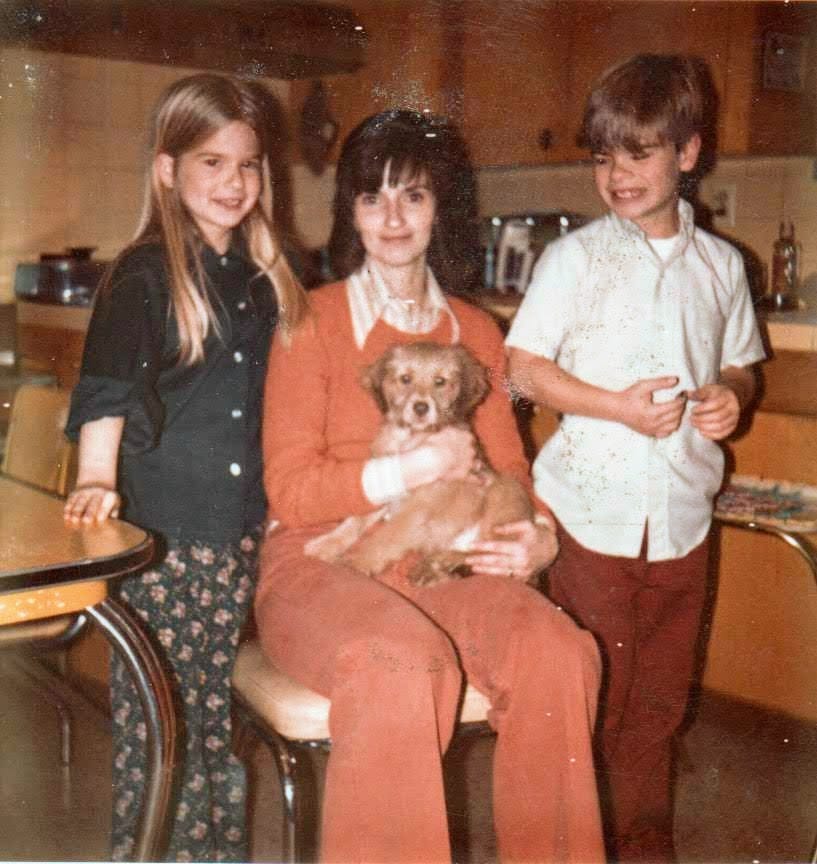

My older brother, Joe, was born on the last day of 1963, five months before President Johnson launched his Great Society; eight years before PBS debuted The Electric Company, which our mother credits with teaching him how to read; and more than a decade before PL 94-142 guaranteed his right to a free and appropriate public education. He lived with our parents until 2018; now, at nearly 61, he lives in a community-based home for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities.

In the 1980’s, our parents attempted to transition Joe to a life outside of their home. After hitting a caregiver, he was kicked out of a group home he didn’t want to live in, and one day, on his way home from a job he clearly disliked, he refused to get off a public bus at the end of its run. He’d been a talkative boy, but by that time he was a nearly mute man and did not respond to the bus driver. The police were called. Joe was handcuffed. “I got arrested,” he told our mother. Years later, she called this a turning point. Decades before activists began drawing lines between police shootings and mental disabilities, my parents feared that their strong, silent, bearded son might be shot by someone who would misunderstand him. Wanting to protect his life they abandoned their efforts to build one for him in the larger world, and so his shrunk.

His days turned into years that turned into decades of a life at home, with our parents as his primary companions. Nearly ten years ago, facing the different threat of their own mortality, our parents joined forces with others caring for adult children to form their own group home. As Joe transitioned to living there–his choice, this time–he blossomed. He is still mute and now mostly bald and completely toothless; deep furrows line his face, and he looks years older than he is. Covid nearly derailed his new life, and keeping it on-track is a persistent challenge for my parents and his caregivers, but today, six years into it, he is happier than we have ever seen him. “You know, Mom,” I said to our mother soon after his move, when we were marveling at his transformation, “no one wants to live with their parents forever.”

How might all our lives have been different if he'd been born 20 or 30 or 40 years later? The question is a door I rarely let myself open.

I wrote the words above for a writing exercise in a class I’ve been taking (Jeannine Ouellette’s School, worth every penny and more). For much of the past two months, I have been writing about my brother Joe, someone I’ve written little about in all the years I’ve been writing.

That door in the last sentence? I didn’t set out to open it when I began the class. It’s more like I leaned against it when we had an assignment to write fairy tales, and it swung open—just a little at first, and then suddenly a lot.

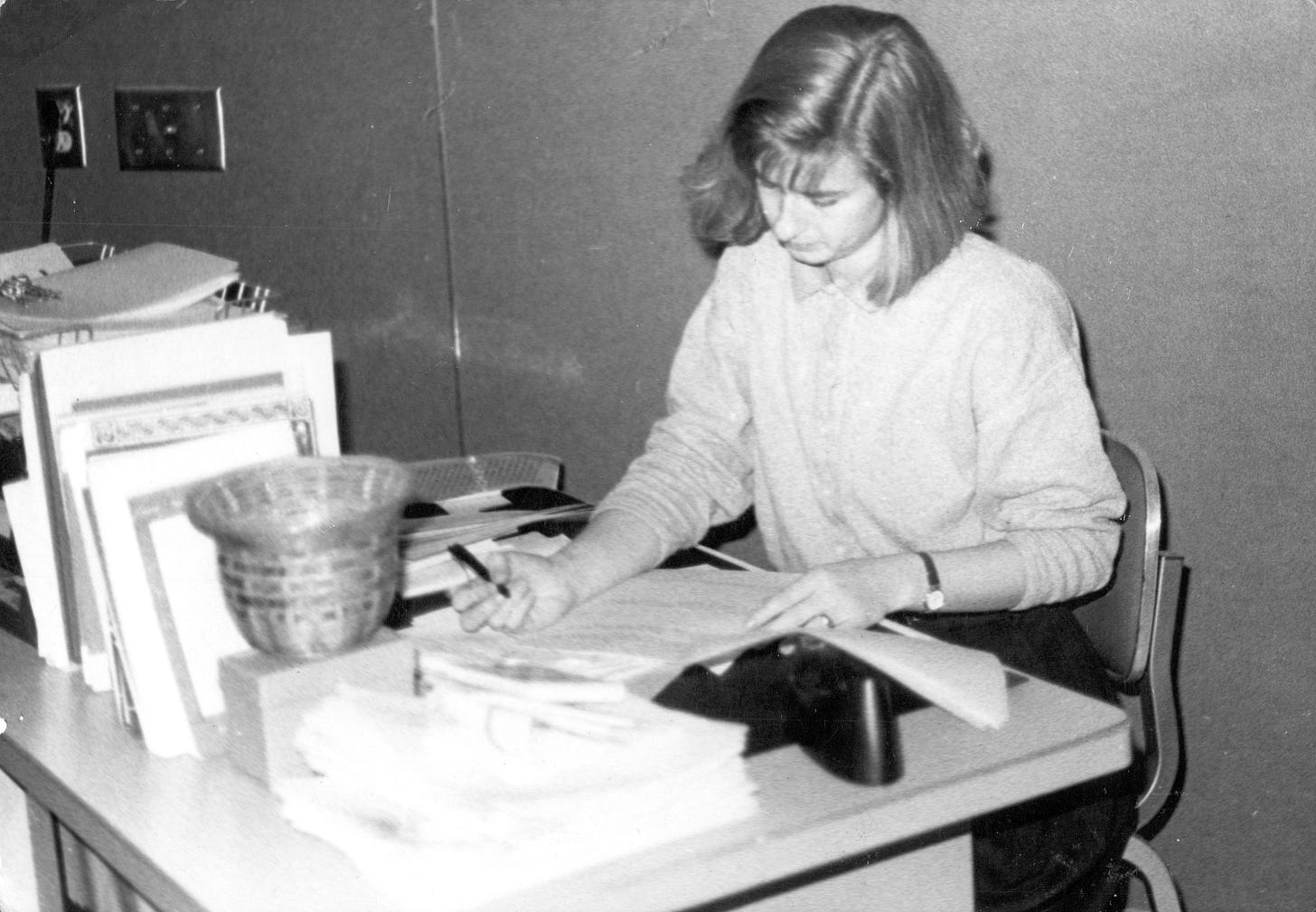

When I retired from teaching and people asked me if I was now going to write, I shrugged. I had been writing, for decades, but I knew what they meant. Writing a blog or a newsletter didn’t seem to count. They meant poetry. They meant books. They meant something that someone else decided was good enough to put into the world. They meant like I’d once done, twenty years ago, like I started doing in 1979, when Seventeen magazine published one of my poems. I usually shrugged and mumbled words that added up to “no” because there was nothing I felt compelled to write about in the ways that they meant.

I wondered if earlier ideas and ambitions I had about writing were things I should let go. Maybe the time for that had passed, a window had closed. I felt a bit frozen by the whole idea of making some kind of big commitment to writing. I shifted my blog to Substack and thought I would focus on the topic of what it means to choose to live a small life. That’s what I had done, to make it possible to retire earlier than I once planned. It’s what I had done to try to find a way to be OK in a world and life that was not working for me—not what I had done because I had a writing project to pursue.

I took Jeannine’s class because I like her and her approach to writing, and I like the other people who gather there. I wanted more of that. That’s all.

I talk on the phone with my mother, and she tells me about the latest meeting with the behavior specialist who is working with Joe, my parents, and Joe’s caregivers to address issues causing problems for him in his home. “I keep thinking,” she says, “about how they told us all those years ago that the two halves of his brain don’t communicate with each other. I think maybe it’s not that he’s being stubborn or difficult when he won’t respond, but maybe it’s just taking him a long time to process what they’re saying.”

“What?” I say. What?

I Google brain hemispheres not communicating and I discover a condition called Agenesis of the Corpus Callosum. I Google agenesis of the corpus callosum and autism. Missing puzzle pieces suddenly materialize and lock into place, but the whole picture changes. It’s like I thought I was putting together a picture of puppy, but now I see that it’s one of an elephant.

I want to sweep my arm across a table and send the puzzle crashing to the floor.

In another phone call, I ask if she knows about agenesis of the corpus callosum. I ask if that’s what Joe has. “Yes,” she says, “I think so. I think that’s what he has. And autism.”

How did I not know this? What else have I missed? What else am I missing now?

My parents and Joe’s caregivers began working with a behavior specialist because Joe won’t allow caregivers to assist him with bathing, and he won’t bathe himself. The only person he will allow to help him is our 81-year-old mother. Twice a week she goes to his home to cajole him into the shower, and every weekend she and my dad bring him back to their house for an overnight visit in which they also get him to shower. Our father, 83, is having some health issues of his own that also require my mother’s increasing support. I live four hours away from them. My husband cannot think of retirement for at least 3 more school years, and I have an adult child I cannot, right now, not at any time that I yet know, move away from.

Life as I’ve known it has begun to feel like a ticking bomb. I don’t know when it’s going to blow or what the size of the explosion will be, but I know that it will.

The exercises in the writing class feel like a portal. I am writing like I never have. For days in a row, I wake up and make a mental list of things I want to do, and then I spend the whole morning writing instead. I am writing about things I’ve never written about, in ways I’ve never written.

I am writing better things than I have ever written.

I would share them here, but for the first time in nearly 20 years, I want to publish in a different way. If I share them here, even in rough form, they will be considered published, and other places in which I’d like to see them won’t consider them. I feel pulled between the writing I want to do here and the writing I am doing there. I feel pulled, but I know I want to go further into the portal.

My brother and I are what some once called Irish twins, born less than 12 months apart. Our birthdates mirror each other: He was born on December 31, and I was born the following December 13th. Today is my 60th birthday.

Milestone birthdays have never unsettled me. I cannot even remember my 50th. It came during a hard time and was just another day. But 60: This one feels unlike any that have come before.

Thanks to the brain injury I sustained in November of 2023; thanks to the smaller life I chose; thanks to recovery enough from the effects of working for than 30 years in a failing system I could never find a way to be OK in; I have had plenty of what I’ve needed in the last 12 months to deeply consider what it means to enter this decade, to be at this place in a life. So many things I might have had are never going to happen now, but I have few thoughts or feelings about that. I am more concerned with what might happen next. I feel a kind of urgency that is new to me.

For the next 18 days, my brother and I will be the same age. For decades I turned away from him; perhaps I ran away from him. It is only just now, these past few weeks of writing about our shared childhood, that I’ve realized the ways in which the picture of each of our lives has always been a reflection of the other’s. I have been wondering what it might do to turn and face that reality, rather than try to escape it.

In her work on inspiration and creativity, Elizabeth Gilbert conceives of ideas as “disembodied, energetic life forms” in search of human collaborators who can manifest them.1 I am not sure of that, but I recognize my recent experiences in these words of hers:

But sometimes – rarely, but magnificently – there comes a day when you’re open and relaxed enough to actually receive something. Your defences might slacken and your anxieties might ease, and then magic can slip through. The idea, sensing your openness, will start to do its work on you. It will send the universal physical and emotional signals of inspiration (the chills up the arms, the hair standing up on the back of the neck, the nervous stomach, the buzzy thoughts, that feeling of falling into love or obsession). The idea will organise coincidences and portents to tumble across your path, to keep your interest keen. You will start to notice all sorts of signs pointing you towards the idea. Everything you see and touch and do will remind you of the idea. The idea will wake you up in the middle of the night and distract you from your everyday routine. The idea will not leave you alone until it has your fullest attention.

And then, in a quiet moment, it will ask, “Do you want to work with me?”

The past few weeks, I have recognized this invitation, and I have been considering my answer to it.

In the past two decades, the years since the publication of my only book, I’ve gotten a few such invitations. It wasn’t so much that I turned them down as that I couldn’t find a way to accept them. It became so painful to let those opportunities go that I changed my address and wrote “Return to Sender” on the few that managed to find me anyway. I told myself I didn’t want to accept them, when the truth was that I just couldn’t.

I don’t want to do that this time.

I am realizing that I no longer have time to fuck around. I am no longer in mid-life. I’ve already had my second chances. I might still feel much like the girl I once was, but I am 60 years old.

Windows are closing, but they are not yet shut. I have some space right now, today, that I’ve never had before. I have some of the energy and capacity such work requires. My resources are limited—hell, they have always been limited, they are always limited, for most of us—but there is a book (or something) within me that wants to be out in a world that is larger than the one of this newsletter. And I want to say “yes” to it.

I am going to say yes.

Gilbert provides a roadmap for how to do this in ways that do not destroy our lives or those of the people we love: “You can receive your ideas with respect and curiosity, not with drama or dread. You can clear out whatever obstacles are preventing you from living your most creative life, with the simple understanding that whatever is bad for you is probably also bad for your work.” (emphasis added)

There is more, but that’s the crux of it.

I can see that in the last three years, so many obstacles have fallen away—and that, likely, is why the invitation is here at all. I can see that more clearing needs to happen. I can see that, for me, right now, the work and the clearing are inextricably bound, and one will serve the other.

As I approach the end of the first year of writing this newsletter, with its focus on small living, I am not sure what this development means for it. I do know that it cannot be a priority in the way I thought it might be when I started it. I will not be focused on growing an audience, developing new offerings, or even committing to a publishing schedule. (All options I have considered and would implement if this were the thing inviting me.) It might not be focused on small living. I might write here only sporadically, or not at all. I don’t know yet if this place is an obstacle or a supportive beam. I will find my way as I continue to go.

I like thinking that this is, perhaps, part of the story I started writing here. Perhaps it is a plot twist I couldn’t anticipate. Perhaps this is what a smaller life can give you—expansion in ways you couldn’t imagine when you embarked on it.

If my change in energy or direction means that you might fall away, please know that is OK. As I look back over 60 years of living, I can see so many people who have come into my life, and then out of it again. Some have come back, some haven’t. I’m grateful for almost all of them (even the ones I hope never return). I am grateful for you who receive the words I share, and I am always so, so grateful for those of you who share yours with me.

I can’t think of a better birthday present to give the girl who was once me, or to the brother she loves more than she ever let herself know.

Happy birthday to us.

As always, you know I love to talk with you in the comments. Please leave one if you’d like to.

And subscribers are always a gift I love to receive.

I am always amazed, every single time I tune in here, at how much what you writes resonates with me. This week I started the process to pursue a SS disability determination for one of my kids, and much of the past year has been spent trying to figure out what this child's future will look like. I am glad to hear that your brother has found some modicum of happiness in where he has ended up.

I send you the happiest of birthday wishes, and I can't wait to see how this creative invitation works out.

Happy birthday, and nice to (virtually) meet you... I've never commented before, but I discovered your writing through reading your heartfelt "In Memoriam" post about the passing of Robert Ward. My family moved to a new address at the end of 2019, and our new address was still receiving letters for The Bellowing Ark Press and for Robert Ward and Paula Milligan. The fact that these weren't forwarded to somewhere else made me curious enough to do some internet searching, which led me to discover some of the wonderful works that have been published by Bellowing Ark, and also to your blog. Seems we'd moved into a home which used to be owned by very interesting people.

It's sad to hear that they have passed on, and your memoriam post had me contemplating life and difficult things, and even tearful for someone I'd never met.

I don't really want to make this too long or derail too much, so I'll say I appreciate your writings very much. It's always nice to rediscover that there are people in the world whose words resonate with me...